SEVEN naughty children once ran around this farm, playing, fighting and growing. Now we are old, we can look back with fondness and gratitude to God who placed us in this family in this valley.

The seven kids were the progeny of Ruth Carte and Judy Carr, two sisters whose husbands toiled to eke out a living in these lovely mountains.

Bill and Ruth Carte bought the Cavern in 1941 in the middle of World War 2. Bill had only one eye (we never found out why) and was declared unfit for active duty. Judge Thrash, a friend, lent Bill and Ruth the money to buy the Cavern. I think they were also helped by Uncle Charles, my godfather, who lived in Zimbabwe and was better off than most his relatives.

Bill and Ruth had worked together and fallen in love at the Oaks, near Richmond. The owner of the Oaks had his eye on Ruth and was not pleased when she preferred bald Bill. They therefore left as refugees.

In his letter of proposal to Ruth, Bill stated his goal: “to build the most beautiful farm in South Africa”.

The Carte kids were: Rosalind, David, Peter and Anthony, born in that order from about 1943 to 1948. Ruth was nicknamed “Maqoembane,” which we understood to mean the cow of many calves.

The Carr kids were Robert (born in 1944), Jane and Harvey. As we grew, we became a tight little clan – us against the kids of the guests.

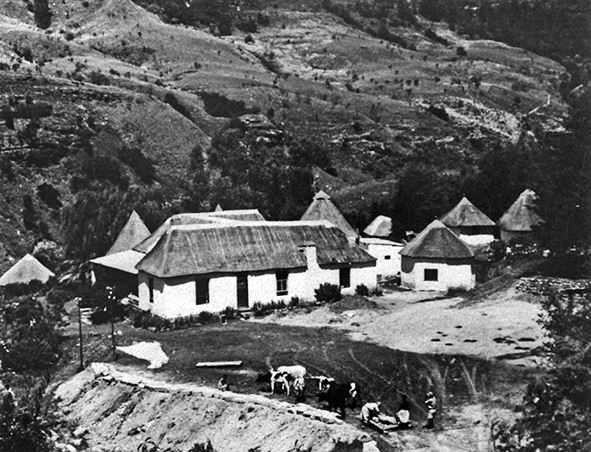

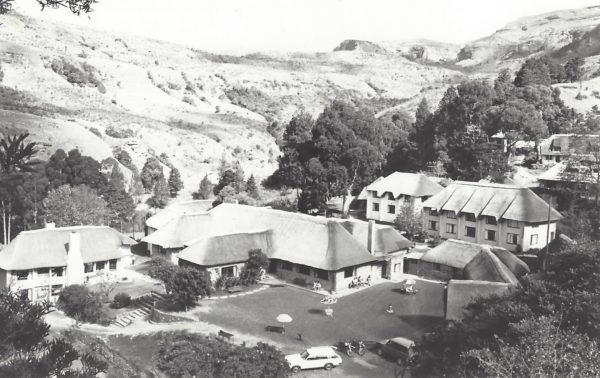

The Cavern in the early days was a guest farm with the emphasis on “farm”.

Our father, Bill Carte, was a hotelier second and a farmer first. Up at the back we had about 80 cattle, mostly dairy cows, sheep, ducks, chickens, turkeys and pigs. Guests were housed in the sandstone main building with a lumpy thatched roof, also in a number of rondavels dotted about.

We grew our own fruit and vegetables, which were displayed annually on the Bergville show and were “highly commended”. We produced our own milk. There was a separator from which Soleelo would extract cream. In the early years there were no fridges but a sort of cold cabinet in which water would trickle over stones to keep things cool.

Ruth Carte could get jelly to set – there, or, if necessary, in the Fern Forest stream, which was cold, summer and winter. Later, paraffin fridges arrived.

We were ahead of most South African farms in having electricity. First there was a pelton wheel driven by a diversion from the Fern Forest stream – our own hydro electric power station.

Later my father bought a Lister diesel and then, memorably in the early 1950s, a mighty 16 horsepower Blackstone diesel engine that would thump away until 10pm or 11pm every night, when my father would hang his boots on a wire in our room and that would choke the great thumper into silence. Thus it was for another 30 years or more before Eskom connected in the 1980s.

In the early days, there was the main building and a number of rondavels dotted about it. There were no “private bathrooms”, rather rows of four bathroomseach for ladies and gentlemen.

After each guest had bathed, Triphene or Constance would whip in and clean it down with Vim for the next person. Guests queued patiently for baths, which drew hot water from a donkey boiler – two 44-gallon drums over a wood fire.

The brochure proudly mentioned that we had water borne sewerage – three loos for the ladies and three for the men.

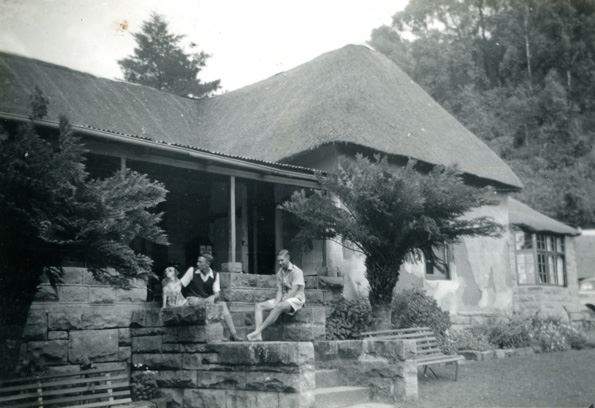

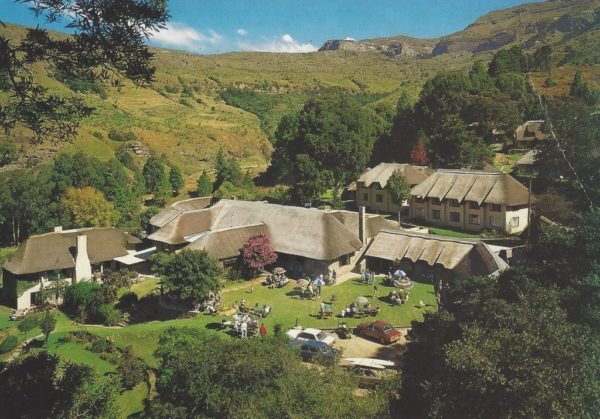

Every year until today extensions and improvements were built.

As kids we had no idea how special our environment was. The glorious mountains, the splendid forests, the rushing streams, the numerous waterfalls, the bushman paintings were all taken for granted.

The farm animals also provided amusement – and horror because we were our own butchers. We all remember Elias, our muscled waiter, walking around jovially with a knife a foot long and his hands covered in blood after doing in one of our enormous Landrace pigs – and our father trying to shoo us away from the bloody scene after he had blown away a large ox with his 12-bore.

Ah, the poultry, How many ailing turkey chickens and ducklings did we kids not try to nurse back to health – to be defied by their own determination to die.

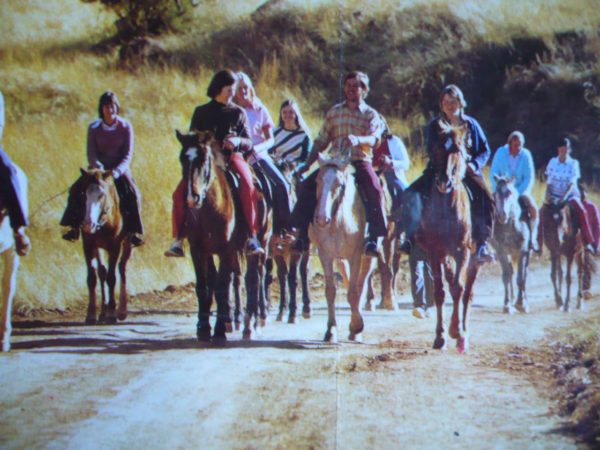

And the horses. Our parents were good horsepeople and gave us every encouragement. We rode at the Cavern and later at Treverton.

Then there was the road, the dreaded road. It was and remains the end of the road. Travelling from Durban, you left the tar shortly after Estcourt. The “main” road through Winterton and Bergville on to the halt was topped with shale and passable most the year. The last nine miles from the halt were a nightmare when wet. Dozens of guests were stuck, or came unstuck, swerving off the road. Pulling them out with the Willys Jeep, or sometimes oxen, was routine for our parents.

The road to Harrismith was also shale-topped and a “main” road. The Oliviershoek Pass occasionally presented a challenge but Bi 11 was the best mud driver in the district and seldom got stuck. I remember swelling with pride when he took the Ford I-ton bakkie through a mud drift in which seven or eight other vehicles were completely bogged.

The Tugela River would often flood the causeway, cutting the Cavern off completely until my dad and old man Van Rensburg built the “Nook” road to circumvent the Tugela up to Oliviershoek Pass. That is today the road to Montusi.

“Rather mud than blood”, my mother used to say. But she never stopped fighting the roads department. Old Mr Boucher with his formidable yellow grader spent half his lifetime improving the road – until the next rains.

Our father, Bill, was a large man with a large voice, which he used to summon the staff with great bellows from the back verandah.

He kept scuffing his bald pate on the top of doorways and I recall him weighing himself in Lamberts, the clothing store in Maritzburg – 220 pounds, a weight that none of his sons ever attained.

He died of cancer when I was nine and Ant was only six, so our memories of him are somewhat faded. He had a kindly disposition and, unlike his sons, never swore.

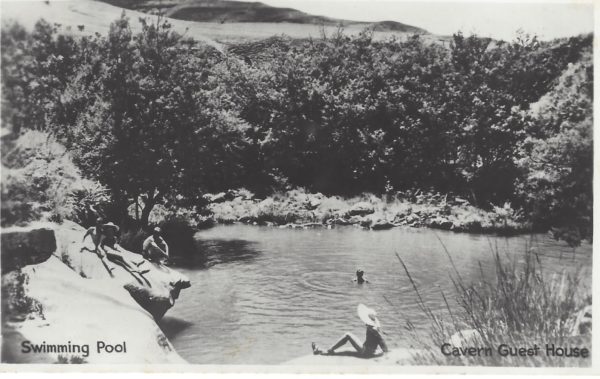

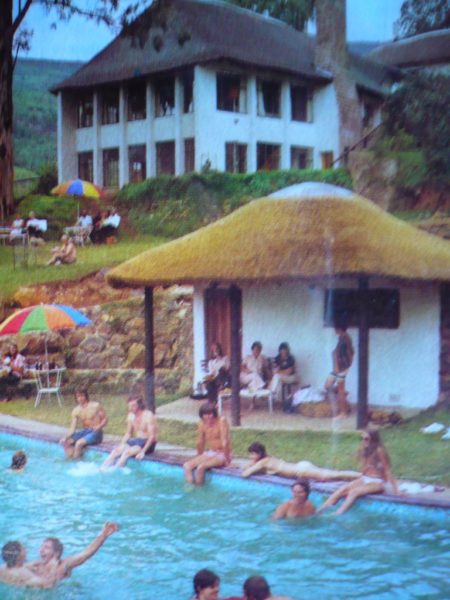

During the war years, before I could remember, we hosted some Italian prisoners of war, who built the first tennis court. Initially the natural pool and the waterfall pool were the only two swimming pools.

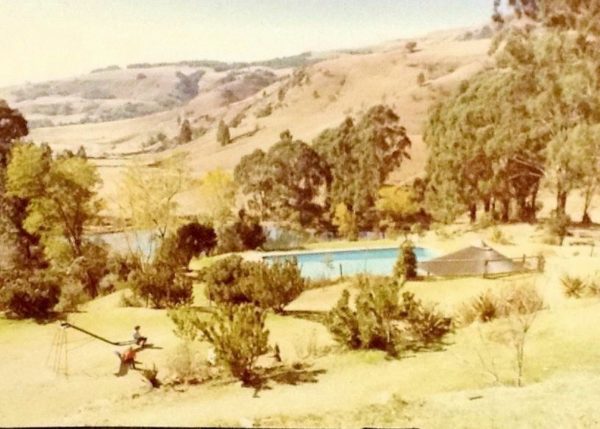

Bill Carte’s last construction project before he died was Charleswood Dam, which is still there below the tennis court. The dam became the main pool for the seven kids. After Dad died, Bruce Carte built a super blue rowing boat for the Carte kids. She was well named Happy Days. My father built us a raft based on two 44-gallon petrol drums. It was wildly unstable and would periodically cast everyone on board into the sea.

We kids had free access to the dam even before we could swim. Ros saved me from drowning. I actually think I was unconscious for a short while but no mention was made of the event. On another occasion during a great sea battle, Rob and I jumped from the boat on to the raft to take prisoners. Harvey jumped off. He couldn’t swim and went straight to the bottom. Rob and I pulled him out. No-one banned our game. On another memorable occasion a water snake chased Harvey right to the top of a pole at the end of the jetty.

Every summer Sunday the whole guest house would move down to the natural pool for a picnic. Typical English speakers, we were clueless about braaing. Everyone would impale his or her meat on a green wattle stick, sear it in the flames and eat it before it was cooked. No-one thought about a grill, or allowing the fire to burn down to coals.

Before we could swim, we envied those who could frolick around in the Big Pool, while we paddled around the shallows and kept slipping on brown slimy stuff. My first hero was Bill de Jager, who had a cow’s lick in his hair and, at 7, swam around the big pool like a dolphin. Ros was the first of us to swim across first the freezing waterfall pool and later the big natural pool.

Our parents left us in the care of Zulu au pairs for much of the day. All seven of us were taken “samben” (come with us) after breakfast and lunch. This involved a short walk to a variety of locations, then playing all morning or afternoon. We boys prized our Dinky toys. We’d make roads and vroom vroom for hours on end. We learned to cut the tops off wattle trees, take a forked stick, pull back the green wattle and let go. Poor Ros once stood in the wrong place and took the forked stick behind the ear.

The wattle and gum forests were full of a strange fungus plant that, when hurled, gave off clouds of yellow dust. These made excellent missiles, which we aimed periodically at passing guests.

We saw our parents only four times a day – at tea time in bed early in the mornings and at all three meals. I remember my father was a keen chess player and couldn’t get over the hours he and regular guest Courtney Edmonds sat staring at the board.

Sibling rivalry was intense. My ghastly little brothers kept stealing and spoiling my stuff. Once Peter deliberately broke the spokes of my prized tricycle, which was so high tech that it had a chain. I therefore occasionally had to administer a bloody nose to one or other of the little brothers.

They would occasionally gang up on their big brother. Sometimes I would push Peter aside when he was hassling Ant. Then the two of them would fall upon me with fists and shoes.

This non-stop bickering and fighting was a feature of Cavern life until we reached puberty and girls became more important than the stuff we owned. Another reason we gave up fighting was that eventually the brothers were as big as I.

After my father died, dozens of people who really loved my mother, stepped forward to help her. Kate Nettleton came as a guest and joined as a staffer, becoming Mum’s right hand right until she died. Natalie van Rensburg stepped in to fill that void, also until she died. Mary Woodrooffe came in and transformed the Cavern garden into an Eden. You have never seen shrubs, flowers and peach trees like it.

Walter Smith, Mum’s engineering friend, did a project every Christmas holiday. First he built the Cavern pool, then the bowling green. We didn’t have a tractor, so all the excavation was done by oxen and dam scrapers. Both the pool and the bowling green were excellently built. The bowling green was criss-crossed with French drains, which were filled with stones. It drains well to this day. Next he built the tennis courts. This was all on his annual holiday.

Those helpers enabled Mum to keep the Cavern going and not to seek work as a matron in a boarding school.

Gradually the teen years overtook us. Precocious Rob Carr collected pictures of Hollywood stars such as Ava Gardner and Marilyn Monroe and enthused about their thoraxes. These delights were lost on us for a while but eventually the penny dropped.

Then dawned rock ‘n roll.

I remember vividly returning to Treverton, aged about 11.The biggest jolla in the school, one Dawny Hatton (13) from Estcourt, came back from the hol’s with his long dark hair swept back into a DA (duck’s ass). There was a wind-up record player at the school and Dawny introduced us to Elvis, singing along raucously to Ready Teddy, TuttiFruiti and Blue Suede Shoes.

The next huge leap forward in our development was the arrival of a real electric radiogram with an amplifier. That made our records sound so much better. The first hi-fi with two speakers and stereo arrived in 1959, totally transforming the Cavern dance.

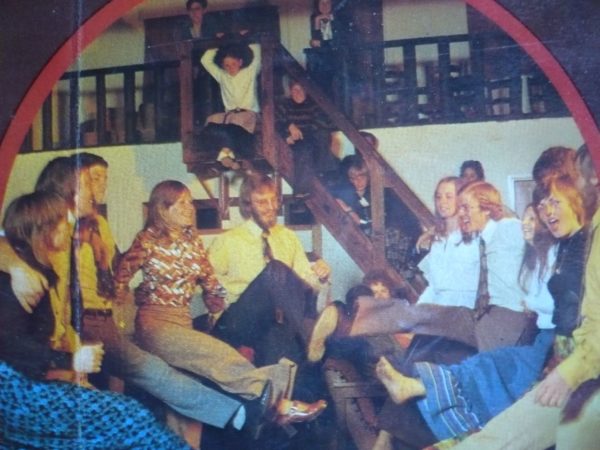

When we became teenagers, the adults were allowed the first two hours of the dance, after which the teenagers ruled. Many guests came year after year and we became friends and would-be lovers of their kids. Their kids also brought rock records.

My siblings and I were not great dancers. We were a bit inhibited but some of those visitors belonged in Jailhouse Rock. The Fulton boys were three or four years older than we and were kings of the Cavern whenever they visited. We gnashed our teeth unable to make an impression on wondrous teenage girls in 90-yard starched petticoats.

A few years later our day would come and, so long as the Fultons stayed away, we came to rule the roost. If you went back to school having kissed less than three girls, you regarded the holiday as a failure.

It was on night walks that most courtships began. Our mad Uncle Roddy started the night walking phenomenon when we were quite small. He would take the seven of us out down the road by torchlight, then switch off the torch and run home with the kids squealing and giggling in terror behind him. Those walks were gradually extended and by our teenage years, went all the way to the natural pool.

We were often love-struck and continued many of the holiday romances with letters from school, often over many months. We were fortunate that, unlike others in the boarding establishment, we did not have to send ourselves Valentine’s cards.

By David Carte

Hi there. Did you have a Zulu man living on your farm who would fetch the milk on an ox wagon? His name was Kombi. It was around the mid 1960’s. I know it’s a long shot. He changed my life.

Kind regards

Keith Bosenberg

[redacted]

Many thanks, Keith.

Our dad remembers Sollelo, Paulus and Setta but no ox wagon so perhaps it is another farm?

Wishing you all the best,

Megan